Fort Mosta

(continued)

Ancient Strategic Site

Fort Mosta occupied the cliff face on the spur of land at the mouth of Wied il-Ghasel and was apparently built (according to available documentation and some archaeological evidence) on the site of a Bronze Age citadel and village which was recorded by George Grognet de Vasse (1773-1862), a French Architect resident in Mosta who designed and built the Rotunda church of St Marija Assunta in Mosta. If any such remains had existed at all (and this is debatable) the British military certainly showed no concern for the antiquity of the site, and simply requisitioned the whole area for defence purposes.

Fort Mosta occupied the cliff face on the spur of land at the mouth of Wied il-Ghasel and was apparently built (according to available documentation and some archaeological evidence) on the site of a Bronze Age citadel and village which was recorded by George Grognet de Vasse (1773-1862), a French Architect resident in Mosta who designed and built the Rotunda church of St Marija Assunta in Mosta. If any such remains had existed at all (and this is debatable) the British military certainly showed no concern for the antiquity of the site, and simply requisitioned the whole area for defence purposes.

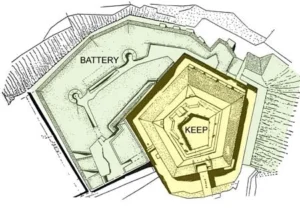

Like most of the forts of this period, late in the history of fortification, the design of Fort Mosta was tailored around its perceived role, and the armament considered suitable for the task. Initially, this was to consist of seven 64-pdr smooth-bore muzzle loading guns mounted inside protective vaulted casemates. Seven other guns proposed to be installed on disappearing carriages were, however, never mounted. Presumably these were to be mounted within the outer battery. Two other casemates, conceived and built in Haxo style, were situated on the west side of the outer enceinte and were designed to enfilade that part of the escarpment overlooking Targa Battery.

Gun embrasures opening from the casemates, had serrated cheeks and surfaces, designed to help deflect incoming cannon shot, while buttresses on the east north east face acted as traverses. Unlike most of its sister defences, Fort Mosta was not intended to be armed with the heavy RML guns, mainly because it was conceived primarily as an inland fort with no coastal defence role.

The Pentagonal Keep

Undeniable, the most structurally imposing and defining feature of Fort Mosta is its keep. Like most other British forts from the period, it is not known who actually designed the structure. The Commanding Royal Engineers at the time was Col. T. Murrey, but more likely than not the whole design and construction process involved the whole engineering staff and cannot be attributed to any one individual. The only two other contemporary forts that were given a polygonal type of keep were those of Bingemma (1875-78) and San Leonardo (1875-78). The latter bears some similarity in the form of its diamond-shape plan, and the shape of its parapets, but this lacks both the scale and the towering command of the Fort Mosta keep. Furthermore the Fort Mosta keep is more than just a place-of-last-resort, as employed in the two earlier forts mentioned above. Indeed, considering its comparatively large size and its many casemated gun emplacements, the keep at Fort Mosta can easily pass off as a veritable fortress in its own right. In this regard, its design may, as a matter of fact, have been directly influenced by the plan of Fort Tombrell, a hexagonal work of fortification (shown below) which was proposed for the defence of the Delimara peninsula in the south of Malta but never built, its place eventually taken by another larger land fort, Fort Tas-Silg built in 1879-83 (a special article on Fort Tombrell is scheduled to be featured on MilitaryArchitecture.com in the coming months). Therefore, rather than being simply a keep, the structure was actually the original fort and only became a ‘keep’ at a later stage in the design process when the outer detached ward, or battery, was thought necessary and grafted onto the position to give it its present shape. Further research, however, is necessary before any conclusions can be drawn on this matter.

and defining feature of Fort Mosta is its keep. Like most other British forts from the period, it is not known who actually designed the structure. The Commanding Royal Engineers at the time was Col. T. Murrey, but more likely than not the whole design and construction process involved the whole engineering staff and cannot be attributed to any one individual. The only two other contemporary forts that were given a polygonal type of keep were those of Bingemma (1875-78) and San Leonardo (1875-78). The latter bears some similarity in the form of its diamond-shape plan, and the shape of its parapets, but this lacks both the scale and the towering command of the Fort Mosta keep. Furthermore the Fort Mosta keep is more than just a place-of-last-resort, as employed in the two earlier forts mentioned above. Indeed, considering its comparatively large size and its many casemated gun emplacements, the keep at Fort Mosta can easily pass off as a veritable fortress in its own right. In this regard, its design may, as a matter of fact, have been directly influenced by the plan of Fort Tombrell, a hexagonal work of fortification (shown below) which was proposed for the defence of the Delimara peninsula in the south of Malta but never built, its place eventually taken by another larger land fort, Fort Tas-Silg built in 1879-83 (a special article on Fort Tombrell is scheduled to be featured on MilitaryArchitecture.com in the coming months). Therefore, rather than being simply a keep, the structure was actually the original fort and only became a ‘keep’ at a later stage in the design process when the outer detached ward, or battery, was thought necessary and grafted onto the position to give it its present shape. Further research, however, is necessary before any conclusions can be drawn on this matter.

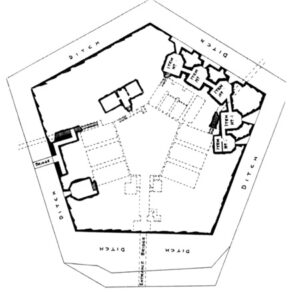

The main defensive elements of the Fort Mosta keep were its enveloping ditch, which isolated the keep from the outer enceinte and also from the mainland to the rear, and three counterscarp musketry galleries which provided the necessary enfilading fire, and were linked to the keep by means of an underground tunnel. One of the counterscarp galleries occupies two faces of the counterscarp wall, creating, in effect, a total of four sets of firing positions, each containing a central embrasure for a 24-pdr S.B. B.L. carronade and six musketry loopholes. All the galleries were protected, externally, by a shallow drop pit revetted in concrete. Entrance into the keep was through a main gateway situated in the middle of the south face and this led directly into a spacious central courtyard. The gate was served by a Guthrie rolling drawbridge, which hasn’t survived, and was flanked by a small defensive musketry position containing three loopholes.

The main defensive elements of the Fort Mosta keep were its enveloping ditch, which isolated the keep from the outer enceinte and also from the mainland to the rear, and three counterscarp musketry galleries which provided the necessary enfilading fire, and were linked to the keep by means of an underground tunnel. One of the counterscarp galleries occupies two faces of the counterscarp wall, creating, in effect, a total of four sets of firing positions, each containing a central embrasure for a 24-pdr S.B. B.L. carronade and six musketry loopholes. All the galleries were protected, externally, by a shallow drop pit revetted in concrete. Entrance into the keep was through a main gateway situated in the middle of the south face and this led directly into a spacious central courtyard. The gate was served by a Guthrie rolling drawbridge, which hasn’t survived, and was flanked by a small defensive musketry position containing three loopholes.

A secondary gateway, more of a sally-port really, lead down into the ditch of the keep and was designed to provide communication between the keep and the adjoining battery. This may, in fact be a later addition, given that the masonry facade with its four adjoining loopholes, are fitted within a projecting concrete slab that buttresses the whole west side of the keep. The secondary gate was served by what appears to have been a chain-and-tackle type of drawbridge.

This heavy buttressing, as a matter of fact, is present throughout various parts of the forts and reveals that very early in its service, the original structure erected in 1878 had to be stiffened to counter the instability created by the largely clayish terrain on which the fort was built.

A walk through the ditch quickly reveals that, in some areas of the fort, the foundations were laid upon a thick concrete raft resting on a layer of clay. According to Hyde, the fort was built over a very yielding layer of Blue Clay whilst the solid lower Coralline Limestone was so very near that it formed part of the adjoining ditches. Indeed the fort bears many marks of structural instability as can be attested by the large number of buttresses reinforcing the revetment of both the keep and the outer battery.

Upgraded armament

In I866, it was recommended that two 6-inch breech loading guns be mounted within the fort, one on the western outerwork and the other on the site then occupied by the useless Haxo casemate (0’Callaghan & Clarke, I886). The two 64-pdrs in the right casemates overlooking Madliena were proposed to be replaced by two 6-pdr QF guns, while the counterscarp flanking galleries were to be armed with 32-pdr SB, B.L. guns.

In I866, it was recommended that two 6-inch breech loading guns be mounted within the fort, one on the western outerwork and the other on the site then occupied by the useless Haxo casemate (0’Callaghan & Clarke, I886). The two 64-pdrs in the right casemates overlooking Madliena were proposed to be replaced by two 6-pdr QF guns, while the counterscarp flanking galleries were to be armed with 32-pdr SB, B.L. guns.

Despite these alterations, Generals Nicholson and Goodenough, in 1888, remarked that Fort Mosta was not a satisfactory defensive work for the important strategic position that it occupied:

“Fort Musta is not a satisfactory work, but the position is a commanding one, and when re-armed, as proposed, it will fulfil its object. It would not be worthwhile to incur the expense of reconstructing it. We think that the 5- 32pr. S.B. B.L. guns proposed to be supplied for flanking ditches might be omitted, and 3-pr. Q.F. guns on field carriages substituted for 6-prs’

However, it would seem that the counterscarp galleries never received their smooth-bore 32-pdr breech loading guns. Two gun emplacements for 6-inch BL guns on hydro-pneumatic disappearing carriages, on the other hand, were constructed on the outer ward of the fort accompanied by their underground magazines, stores, and guncrew shelters.

Construction Materials

Like most of the first-generation British forts of the 1870s, Fort Mosta was constructed from a hybrid combination of masonry, hewn rock, earth, and cast-in-place mass concrete elements.

Like most of the first-generation British forts of the 1870s, Fort Mosta was constructed from a hybrid combination of masonry, hewn rock, earth, and cast-in-place mass concrete elements.

The initial concrete was employed largely in the revetments along the scarp and counterscarp walls, and in the formation of a raft foundation over which various elements of the structure were built (in parts of the battery). The other elements which were built in concrete were the two gun emplacements for the 6-inch BL guns, but these were added later in the 1890s and use a more compact mixture. The casemated gun emplacements, vaults, gateway, and various underground magazines, on the other hand, were constructed in masonry and covered over with a thick layer of protective earth.

At Fort Mosta the original concrete was used un-reinforced and cast in lifts of approximately the same height. The concrete walls do not display any expansion joints although, in various places, and at somewhat irregular intervals, these are perforated with small rectangular holes, particularly at the horizontal interface of the concrete wall and the underlying masonry or bedrock. This seems to suggest that the openings served as weep-holes rather than as anchor points for formwork ties. Most of the concrete revetments in the Malta fortifications from the 1880s, the revetments at Fort Mosta have lost their smooth cement surface finish (owing to deterioration), to reveal cast layers of hardstone aggregate of non-uniform grading. A significant proportion of this aggregate is quite elongated and the proportion of the aggregate appears rather low. Similar method of concrete construction can be found in the walls or ditch revetments of Fort Bingemma (1875), Fort San Leonardo (1878) and the Dwejra lines (1881) and the 100-ton gun batteries at Cambridge and Rinella.

An important element in the design of Fort Mosta comprises the thick earthen mounds which form the large parapets covering the keep and adjoining battery. This terreplein was formed from a rather coarse, dry mixture of stone chippings (varying considerably in size and often obtained during the excavation of the ditch), combined with earth and soil. Along most of the revetments (except for two of the rear faces of the keep, the thick earthen parapets are revetted with a masonry skin of hardstone capstones laid in an inclined plane on the exterior slopes, a technique which was first employed in Malta on the Corradino Lines in 1872. Such a covering helped hold the earthen fill in place, and prevented it from being carried down into the ditch below by torrential downpours.

Where employed as a surface finish, particularly on the external elements of the fort’s walls, the masonry used was of the drafted type, with flat bossing in low relief (known in Maltese as ’bunja’), creating an overall rusticated feel that was popular with the Royal Engineers and was employed in most military buildings of the period. In most cases, the softer Globigerina Limestone was employed while a harder quality stone, the Coralline Limestone, greyish-white in colour, was often employed in capstones of the exterior slopes of revetments and in various secondary features. Amongst those features built in hardstone one finds the revetted cheeks of the embrasures of the Haxo-type casemates and its rear walls, and the various buttresses which were added to stiffen various parts of the enceinte.

Change of Role

With the abandonment of the Victoria Lines as an inland defensive position during the early years of the 20th century, Fort Mosta lost most of its military value, unlike the other two forts on the Victoria Lines, which were retained in use in a coastal defence role. By 1940, the fort was being used simply as a munitions depot, a role which it has continued to fulfil up to the present day.